The Newly Discovered Musical Composition by Handel:

Gloria in excelsis Deo

Gloria in excelsis Deo (HWV deest; "deest" in latin means

"missing", as in missing from the Handel thematic catalog) is a newly discovered work by Handel and Handel and

was found at the

Royal

Academy of Music's (RAM, London) library. The manuscript -- not in Handel's hand

but bound in a collection of Handel arias owned by singer William Savage

(1720-1789) and left to the Academy by his student RJS Stevens on his death in

1837 -- was identified

by Professor Hans Joachim Marx of Hamburg, Germany. Handel may have composed it

during his early years in Germany prior to his departure for Italy. Handel later

borrowed from the Gloria to compose Laudate pueri dominum

and Utrecht Jubilate. (Click

here for

the RAM's press release.) was found at the

Royal

Academy of Music's (RAM, London) library. The manuscript -- not in Handel's hand

but bound in a collection of Handel arias owned by singer William Savage

(1720-1789) and left to the Academy by his student RJS Stevens on his death in

1837 -- was identified

by Professor Hans Joachim Marx of Hamburg, Germany. Handel may have composed it

during his early years in Germany prior to his departure for Italy. Handel later

borrowed from the Gloria to compose Laudate pueri dominum

and Utrecht Jubilate. (Click

here for

the RAM's press release.)

The work is composed for soprano, 2-part

violin, and basso continuo. (It is not a choral work as erroneously reported by The

Times. See below.) It consists of 7 movements and when performed lasts

approximately 15-20 minutes.

A modern edition is available from King's

Music. (For information about this edition, click here.)

On 11 June 2001 Bärenreiter

issued an edition of the Gloria; it is edited by

Hans Joachim Marx.

The August 2001 issue of

Early

Music includes an article/paper written by Professor Marx titled "A

newly discovered Gloria by Handel" (pp. 343-52).

The first private performance (albeit incomplete) of the Gloria

(Domine Deus and Quoniam sections only) was given by soprano Rebecca

Ryan, other students of the Royal Academy of Music, and Nicholas McGegan (conductor) in

London on 15 March 2001.

The world premiere, full public performance of the Gloria was given

by Patrizia Kwella (soprano),

Fiori Musicali, and Penelope Rapson (artistic

director) on 18 May 2001 at the Hinchingbrooke Performing Arts Centre in

Huntingdon, England.

Other noteworthy performances:

-

3 June 2001: The International Händel

Göttingen Festival. Dominique Labelle (soprano) was accompanied by the Philharmonia

Baroque Orchestra (San Francisco) and Nicholas McGegan (conductor).

-

7 June 2001: St Marylebone Parish Church, Marylebone Road, London. Rebecca

Ryan (soprano), the Royal Academy of Music Baroque Orchestra, and Laurence

Cummings (conductor).

-

22 July 2001: Killaloe Music Festival (near

Limerick), Republic of Ireland -- the Irish premiere. Mary Nelson

(soprano), the Irish

Chamber Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan (conductor).

-

15 September 2001: Berkeley, California. North American premiere.

Christine Brandes (soprano), the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, and Nicholas McGegan

(conductor). A special program "in support of the victims of the terrorist

attack and their loved ones."

-

13 October 2001: Toulouse

les Orgues (festival). Sophie Karthaüser (soprano), European Union Baroque

Orchestra, Roy Goodman (conductor)

-

21 October 2001: The Handel Choir of

Baltimore.

-

17 November 2001: Italian premiere in Milan. Lynne Dawson (soprano),

Ensemble Réjouissance.

-

17 January 2002: The St. Paul Chamber

Orchestra (Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota) under the direction of their new Baroque

Series Director,

Nicholas McGegan.

-

18 May 2002: The Bach Sinfonia (Washington, DC) under the direction of

Daniel Abraham.

Available Recordings

For more information about recordings, please visit the new releases page.

|

|

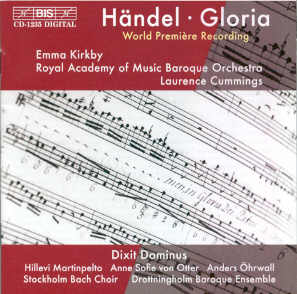

The BIS

label recorded the Gloria in Excelsis Deo on 3 May 2001 with Emma Kirkby, The

Royal Academy of Music's Baroque Orchestra, and Laurence Cummings (conductor). This

recording is coupled with a re-issue (11/86) of Handel's Dixit Dominus with

singers Hillevi Martinpelto and Anne Sofie von Otter and the Drottningholm Baroque

Ensemble and Anders Öhrwall (conductor). The catalog number is BIS-CD-1235, and was released in the UK on 4 June 2001.

|

|

|

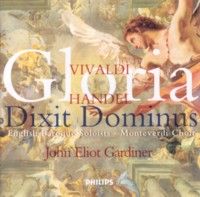

Gillian Keith (soprano), The English Baroque Soloists, and Sir John Eliot Gardiner

(conductor) recorded the

work for Philips in June 2001; together with Handel's Dixit Dominus and Vivaldi's Gloria

(RV 589). This recording was released in October 2001. |

|

|

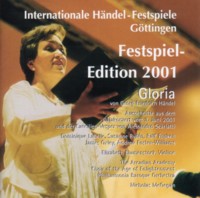

The

Göttingen

Handel Festival and Society have

released a live recording (from the 3 June 2001 gala performance) of Handel's

Gloria

in excelsis Deo with Dominique Labelle, soprano,

The Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, and conductor Nicholas McGegan. |

|

|

Suzie LeBlanc (soprano), L'Académie Baroque de Montréal (period instruments),

and

conductor Alexander Weimann present works by Handel, JS Bach, and Vivaldi.

ATMA Classique ACD2 2215 |

|

|

Julianne Baird (soprano), The Queen's Chamber

Band (period instruments).

Lyrichord Early Music

Series LEMS 8055 |

Press about

the Gloria

(in reverse chronological order)

(Please be aware that erroneous statements exist in some of these articles.)

Christian Science Monitor

29 June 2001

A lost Handel score is discovered - or is it?

By Benjamin Ivry - Special to The Christian Science

Monitor

(NEW YORK) A new recording of a previously unidentified work by Georg

Friedrich Handel (1685-1759), the composer of Messiah, Saul,

Israel in Egypt, and other beloved baroque hits, has the music world in a

controversy that is nearly too hot to, well, handle.

In March, a manuscript score in the library of London's Royal Academy of Music

was identified as that of a previously unknown work by Handel. The 16-minute

Gloria for soprano and orchestra was found by Prof. Hans Joachim Marx of the

University of Hamburg in Germany, in a collection of arias by different hands,

including Handel. Experts date the score to about 1707, when Handel left his

native Germany for Italy.

The score has been recorded for BIS records (on BIS-CD 1235 or see www.bis.se) and features veteran British singer

Emma Kirkby accompanied by the Royal Academy of Music Baroque Orchestra (www.ram.ac.uk).

Yet despite these joyous events, some dissident voices are being heard.

Penelope Rapson, leader of the British music group Fiori Musicali, which gave an

early live performance of the Gloria, finds the piece "a good one and

well worth performing," but does not feel it is by Handel. Ms. Rapson explains

that "it is curious" that this work should survive in the library of someone

from Handel's circle without the composer himself having a copy, as Handel was

"meticulous about keeping manuscript copies of his music."

Among other oddities, she notes that "the music lacks the sure touch of Handel.

Even early Handel ... has a direction and harmonic drive, which this piece in

places lacks. Handel's writing for the voice is more sympathetic." She observes

that parts of the Gloria "are both ungrateful to sing and lacking in

overall harmonic and structural direction."

Other listeners disagree. Curtis Price, a musicologist and Principal of the

Royal Academy affirms, "Basically, every Handel expert that I know of believes

this to be by Handel because the Gloria includes passages that occur in

other Handel works, because the style is right for Handel circa 1707, and

because one of the manuscripts in the Royal Academy Library (hitherto overlooked

by most scholars) actually attributes the piece to Handel.

"What convinced me, upon first looking through the manuscript several months

ago, was the Qui Tollis section. This is vintage Handel, even though he

composed it when only 21 or 22!"

Indeed, the Qui Tollis movement is reminiscent of the well-known chorus All We Like Sheep from Messiah.

Prof. Michael Talbot, a Handel expert at the University of Liverpool in England,

says, "I was convinced of Handel's authorship by the style alone, and

information from Professor Marx received since then ...makes me even more

certain," Professor Talbot says. "The evidence should convince even the

doubters."

The discovery has also opened the field to some energetic Handel bashers, mainly

in France, where the disdain for Handel is unlikely to be altered by this new

discovery. Eminent Parisian music critic and author Jacques Drillon says that

even in Handel's most famous works, the composer was "a baroque version of the

Spice Girls...."

Other, less wildly insulting listeners admire the Gloria as music,

without worrying about who wrote it.

The soloist herself, Ms. Kirkby, agreed to record the Gloria, she

reveals, not because of the Handel attribution, but because the score looked

"interesting, varied, and rewarding to sing, not unfamiliar in the context of

other Handel church pieces I have sung."

Kirkby says that the piece has individuality and charm, good bravura moments,

and, more important, some moments of depth, beauty, and poignancy.

"Everything, in short, that one might expect of a Gloria in the hands of,

at the least, a great craftsman," Kirkby says.

Kirkby finds the current controversy "partly amusing, partly regrettable [that]

a 16-minute piece of fine music is burdened with the hopes and insecurities of

so many people - academics, record companies, even journalists."

If someone manages to prove beyond doubt its authorship, Kirkby won't mind.

"I'll be delighted," she says, "either by the thought that we have one more

piece of [his], or, if not, that the real composer will be identified after all

this time."

Guardian (London)

4 June 2001

London debut for newly found Handel score played

Maev Kennedy, arts and heritage correspondent

Musicians from the Royal Academy of Music have been rehearsing in Handel's old home in

London, for the delayed English premiere of his Gloria in Excelsis Deo. George

Frederick Handel is about to have a sensational week, albeit three centuries late.

The world premiere of the 15-minute piece, which was found three months ago, was given

yesterday at the Handel Festival in Göttingen in Germany. It is released on disc today by

the academy's Baroque Orchestra. On Thursday the academy will give the first known British

performance - unless Handel hummed it at home in Brook Street.

The discovery of a major seven-movement composition, whose existence was unknown to

music historians, was both a source of rejoicing and acute embarassment to the academy. It

was found by a leading Handel scholar, Hans Joachim Marx, not in a dusty attic, but bound

in a volume including several Handel arias, in the academy's library.

The Hamburg scholar's attribution has been backed by international experts.

Curtis Price, principal of the academy, described the music as "fresh, exuberant

and a little wild in places, but unmistakably Handel," adding that it was

"embarassing that such an important piece was found under my nose".

The Gloria is believed to have been a commission in 1707 from Handel's wealthy patron,

Francesco Maria Ruspoli, when the composer was working in Rome. The manuscript, however,

is a much later transcription in another hand. It is thought to date from 1730, when

Handel was already well established in his comfortable new house in Brook Street.

It is possible that the piece had a previous unrecorded London performance at Brook

Street. Handel is known to have held recitals there.

The house, a few yards from Bond Street, was rented and the composer lived modestly,

possibly deceptively so. An Italian visitor who dropped in unexpectedly, was invited to

share a simple supper. Half way through the meal the composer leapt up, said he had had

"a thought", and rushed to a

room at the back of the house. His visitor tiptoed to a window with a view of the back

room, hoping to see the composer at work - only to see him feasting on roast duck and

Burgundy.

The performance, with the Baroque Orchestra and soloist soprano Rebecca Ryan, will be

at St Marylebone parish church, and will be used to raise funds for the Handel House

Museum, which opens in November and the academy's new exhibition centre.

Independent (UK)

16 March 2001

Handel score gets first performance

By Michael Church

A memorable week for Handel included the first presentation yesterday of a previously

lost work discovered in the Royal Academy of Music.

The performance of the German composer's Gloria followed the revelation on Wednesday

that Mozart's re-working of his oratorio Judas Maccabaeus had been found in a

local authority archive in Halifax, West Yorkshire.

Yesterday Professor Curtis Price, principal of the Royal Academy in London, presided

over the presentation of a fragment of Gloria which had been found in the academy

on a piece of microfilm.

Performed by the soprano Rebecca Ryan and academy students under the baton of Nicholas

McGegan, the first two movements of the piece rang out all the more thrillingly for having

been unheard since 1725. The rest of Gloria must wait until the BBC bring back

their recording from Göttingen, Germany, in June. This was more than enough to whet the

appetite; the soprano lines soared as only Handel's can, their ornamentation held in lucid

control. It may be an early work, but it is vintage stuff. Professor Price said it was

possible more finds could be made.

These are interesting times for Handel in London. Starting next week, the Royal Academy

and Royal College of Music will host the annual Handel festival. In May – as revealed

by The Independent – the Covent Garden Festival will stage a production of the opera Clori,

Tirsi, and Fileno in a gay nightclub in London. Finally, the house where Handel lived

in London for 36 years – 25 Brook Street – is due to open in the autumn as the

Handel House Museum.

"All Things Considered" (National Public Radio)

14 March 2001

Interview with Nicholas McGegan about the Gloria

Interview with Nicholas McGegan about the Gloria

The Times (London)

14 March 2001

Glory in this Gloria

By Rodney Milnes

Rehearsals for a Handel work that has been gathering dust for 200 years are

currently taking place

There are two big questions to be asked about the Handel Gloria that

has resurfaced in the library of the Royal Academy of Music. The music has been

sitting there for more than a century bound into a volume of otherwise

exclusively Handel arias. It has been available on microfilm for more than ten

years. So why did no one spot it before? No wonder that its discovery by a

German scholar has left Curtis Price, the Academy’s principal and himself a

distinguished specialist in Baroque music, in a state of slight embarrassment.

Still, for a day or two at least, it has made the Academy the centre of the

musical world, which must warm the cockles of any principal’s heart.

The second — and bigger — question is, is it really, incontrovertibly by

Handel? When the big guns of scholarship are united, it is not for a journalist

to cast doubts. Nor would I dream of doing so, having heard the last movement in

rehearsal.

It looks like Handel, it sounds like Handel and, for heaven’s sake, it must

be Handel. The fact that the soprano soloist from New Zealand, Rebecca Ryan, the

conductor Laurence Cummings and his Academy students were all having such a good

time at yesterday’s rehearsal for tomorrow’s preview playing through the finale

again and again would tend to support the attribution.

For nearly 300 years, musicians have loved performing Handel: there is an

exhilaration in meeting the challenges that he sets that gives enormous

satisfaction as well as pleasure.

And the challenges are formidable. As I wrote on Monday, the first and last

movements of the seven-section Gloria look incredibly difficult on the

page, and so they are in practice. The vocal writing in the Quoniam

section is characteristically florid, apparently leaving the singer no

opportunity to draw breath.

It was fascinating to hear Cummings asking the bass players to relax the

rhythm very, very slightly so that Rebecca Ryan could snatch a gasp.

But you can understand the temptation to keep on pounding through: the way

the tempo doubles at “cum sancto spirito” is incredibly exhilarating in a

peculiarly Handelian way. Just as exhilarating is the gentle counterpoint in the

brief duet passage for soprano and solo violin, the sort of effect that has

Handelians clutching their sides with hedonistic, near-guilty pleasure.

Before getting too carried away it is worth emphasising that this is not, as

some newspaper headlines and even the BBC’s Today programme have suggested, a

“new Messiah”.

It is a short, 15-minute piece for solo singer (in the soprano range) and

string accompaniment. Scholars agree that it dates from 1708-9, when the

22-year-old Handel, or “il caro Sassone” (the dear little Saxon) as the

Italians hailed him, was perfecting his trade in Rome.

Assorted cardinals were commissioning liturgical music from him, and this

Gloria may be among these commissions. A more important patron was Prince

Ruspoli, in whose palace Handel was based for much of those two years and for

whom he was turning out dramatic cantatas at the rate of one a week.

Many of these were first performed by Margherita Durastanti, the soprano who

was also based at the palace and accompanied the household on the summer jaunt

to Ruspoli’s estates at Vignanello. She later followed Handel to Venice, where

she created the title role in his first big operatic success, Agrippina,

and indeed to London, where she sang in many of his operas (as did the bass

William Savage, from whose collection this Gloria comes).

Were Handel and Durastanti having an affair in Rome? Who knows: Handel kept

his private life resolutely private, but it is probably unlikely.

Charles Burney described Durastanti as “coarse and masculine” (which was

fodder for the fatuous was-Handel-gay school of musicology. Who cares?) and the

librettist Rolli said she looked like an elephant. And who knows who first sang

this Gloria? Durastanti had sung in Handel’s marvellous oratorio La

Risurezzione [sic.] and got into frightful trouble with the Pope. Women were

not allowed to sing sacred music, and certainly not in church. She was

threatened with a flogging.

So maybe the Gloria was first sung by a castrato, and today it is the

likes of David Daniels and Andreas Scholl who should be chasing after it, not

Angela Gheorghiu.

Professor Price thinks not. He plumps for Durastanti, noting that B flat — in

which the Gloria is basically set — was a key in which Handel frequently wrote

for her.

So what next? The last movement that I heard yesterday will be performed by

the Academy of Music’s students at a private press conference tomorrow to launch

the programme for this year’s Göttingen Handel Festival. The Academy emphasises

the word “private”, by invitation only, lest rabid and excluded Handelians stage

riots in the Marylebone Road.

Nicholas McGegan will conduct the whole piece at

Göttingen

in June. That is fitting. It was at

Göttingen

in 1920 that the Handel revival got under way with a performance of his opera

Rodelinda, and since it seems that

Göttingen

is losing out in the battle for funding with Halle, the second full-scale Handel

festival in Germany (just one in Britain would be nice).

So it needs every fillip it can get. Meanwhile, there will be a race to get

the first recording out. It really is that good, and it is a privilege to have

been in at its rebirth.

The New York Times

13 March 2001

A previously unknown choral work by Handel has been discovered by a German

music scholar. It will receive its first known complete public performance when

it is played on June 3 at the Handel Festival in Göttingen, Germany, by the San

Francisco Philharmonic* Baroque Orchestra, led by Nicholas McGegan, a Handel

expert. The work is Gloria in Excelsis Dio, found by Hans Joachim Marx of

Hamburg University while poring through manuscripts at the Royal Academy of

Music in London. Handel (1685-1759) lived in London for 36 years. Portions of

the work, whose discovery was made public yesterday in London, are to be

performed at the Royal Academy on Thursday.

*erratum: should be "Philharmonia"

The Times (London)

12 March 2001

Handel scholar finds the new 'Messiah'

By Dalya Alberge, Arts Correspondent

A German music scholar yesterday recalled the moment that an undiscovered choral work by

Handel appeared in front of his eyes "like a ray from Heaven".

Hans Joachim Marx was trawling through manuscripts at the Royal Academy of Music in London

when he stumbled on the original composition, which is expected to become as significant

as the composer's Messiah.

Professor Marx, of Hamburg University, said that the discovery of Gloria in Excelsis

Deo in a tightly bound collection of the composer's aria sent his heart racing. The

seven-movement work for soprano and strings is thought to have been composed in Rome in

1707.

Scholars have confirmed its authenticity and liken the find to the discovery of

Tutankhamun's tomb for the musicologist.

"The music is very virtuosic, very expressive and full of effects," Professor

Marx said. "I realised its significance immediately. It was a wonderful feeling, a

great moment. But I thought, I have to do a lot of work to prove it." Professor Marx,

acting chairman of the Handel Society in Germany, said that he could not wait to hear it

performed.

Experts predicted that it would become one of Handel's most loved pieces.

Handel (1685-1759) lived for 36 years at 25 Brook Street in Central London, where he

composed Messiah and Music for the Royal Fireworks, and filled the

building with live concerts, workshops and exhibitions. Because it is not documented that

he wrote a Gloria, there is no way of knowing if the work was performed. The

manuscript is thought to have been owned by William Savage (1720-1789), a friend of

Handel, who sang for the composer as a boy treble in the operas, then as an alto and, by

the end of the 1730s as a bass in his operas and oratorios.

The manuscript is an English copy from the 1730s and may be in Savage's hand. It was

through Robert Stevens, a student of Savage, that it made its way to the academy in the

19th century.

Extracts from the piece will be heard at the Royal Academy of Music on Thursday before the

work's first full public performance, at the International Handel Göttingen Festival 2001

on June 3. The BBC will be recording it in July.

At Göttingen, Dominique Labelle will be the soloist, with the San Francisco Philharmonia

Baroque Orchestra conducted by Nicholas McGegan, a Handel specialist. He said: "The Gloria is a gorgeous work, beautifully composed. It will achieve a great popularity. This is the

Tutankhamun discovery for a musicologist."

Michael Talbot, Professor of Music at the University of Liverpool, said: "The quality

of the work is so high that it will surely join the ranks of Handel's most loved music.

For sopranos it will become essential repertoire. They'll be queueing to perform it.

"It has great melodic distinction. The vocal lines are complex and flowing, yet never

degenerate to empty virtuosity. It is a wonderful piece. It's going to make a big

splash."

Donald Burrows, author of the Handel biography in the Master Musicians series and the

catalogue of Handel's musical autographs, said: "This is a very exciting piece.

There's no doubt of its authenticity, particularly because the musical content includes

various melodies and fragments we also know from other contexts of Handel's music."

Professor Curtis Price, the principal of the Royal Academy of Music, said he felt slightly

embarrassed that "such an important piece was found under my nose". However, the

academy houses 150,000 manuscripts and documents of international significance that have

yet to be catalogued.

The Gloria will be displayed for the first time in the academy's new York Gate

Collections, which opens to the public this summer.

The Times (London)

12 March 2001

Choral work to take the breath away

By Rodney Milnes, Times Opera Critic

It may not be quite the same as standing silent upon that peak in Darien for a first

glimpse of the Pacific Ocean, but sitting in the Royal Academy of Music with one's hands

on a piece of music by Handel unseen and unheard for nearly 300 years runs it pretty

close.

Although not in Handel's own writing, it was copied - beautifully neatly - by one of his

singers. The string and vocal lines may be in different clefs, but what the hell: clear

the mind, keep calm and soon you're singing along with one of the greatest composers the

world has known. I know proper journalists are supposed to avoid hyperbole, but in the

heat of the moment there really are no other words to describe Handel.

This Gloria is set in seven movements and probably lasts - with a singer in a

less excited mental state than I - about 20 minutes (I got through it in nearer ten). The

first movement is incredibly elaborate, and fast, with a decorated vocal line that could

come from any of the early operas, or indeed from the liturgical works, such as La

Risurrezione (sic.) and the Dixit Dominus that the 22-year-old was turning

out in Rome. One's first reaction is to wonder where on earth Handel expected his singer

to breathe.

This virtuoso movement returns at the end for the Quoniam, the section to be

sneak-previewed at the Royal Academy on Thursday, giving the whole composition a neat and

logical shape. In between comes a Handelian variety of tempos and forms: the Et in

Terra Pax movement, in gentle triple time, has the feel (or certainly the sight) of O

Thou, that Tellest from Messiah, still 35 years in the future.

But the experts must be right: this exuberant, fresh composition has to date from the

years 1707-08 when Handel was working in Italy. Apart from anything else, music set to

Latin words is rare at any other period of his creative life.

How important is it? Enormously, given that every semiquaver by Handel is important.

Whether it adds to our knowledge of his work as a whole is another matter best kept for,

again, a calmer moment; this was the period when he was turning out dramatic cantatas of

the highest quality by the dozen.

But whatever the final verdict, this "new" piece will give boundless pleasure to

singers and players, as well as to all those who admire a composer whose stock continues

to rise.

A few years ago, when the Handel House in Brook Street, Central London, was in financial

trouble, it was noticed that Jimi Hendrix had lived next door. Someone on an evening paper

had the bright idea of asking the HMV shop round the corner which composer had sold the

most CDs. "Why, Handel of course," came the answer, which was duly published in

the paper.

This politically incorrect and subversive information was suppressed in the later editions

of the paper. It would not need to be today.

Sunday Telegraph (London)

11 March 2001

Lost work by Handel could rival Messiah

By Catherine Milner, Arts Correspondent

An unknown choral work by Handel that some music scholars believe will come to be regarded

as significant as Messiah has been discovered in the library of the Royal Academy of

Music.

Gloria in Excelsis Deo - a substantial seven-movement composition for soprano and

strings - was discovered in a tightly-bound collection of the composer's arias by

Professor Hans Joachim Marx, a leading Handel expert at Hamburg University. The work is

believed to have been composed in 1707 in Rome and has not been performed since then.

Prof Marx, who is also acting chairman of the Handel Society, said: "I was very

fortunate to find this music. It is something very special which happens maybe only once

or twice in a lifetime for every scholar. The music is very expressive and full of

effects. Perhaps not too many sopranos will be able to perform this piece."

Prof Marx discovered the work when attempting to draw up a complete catalogue of Handel's

work for the German government. Several leading Handel experts have examined the piece and

acknowledged its authenticity.

Dr John Roberts, the leading Handel expert at the University of Berkeley in California,

said: "I am convinced that this is an authentic new work. The density of the texture

together with certain rough edges suggests to me that it dates from the very beginning of

Handel's time in Italy. It is certainly a major discovery."

Professor Michael Talbot, a specialist in Italian baroque music from the University of

Liverpool, said: "The quality of the work is so high that it will surely join the

ranks of Handel's most loved music. For sopranos it will become essential

repertoire."

Handel was only 21 when he wrote Gloria. He had left Germany to learn how to

write operas in the Italian style in Rome and was swiftly acclaimed a genius. Having

mastered Italian opera over a period of three years, he moved to London. He remained there

for most of the rest of his life, spending his final years in a house in Brook Street,

Mayfair.

Gloria is believed to have been commissioned by the Roman patron Francesco Mari

Ruspoli. The score was originally in the possession of Handel's friend, the singer William

Savage. It was Savage's pupil, Robert Stevens, who is believed to have given the work to

the academy in the early 19th century.

Professor Curtis Price, the principal of the academy, said: "This is an exciting

discovery, though slightly embarrassing that such an important piece was found under my

nose. The music is fresh, exuberant and a little wild in places, but unmistakably

Handel."

The work will be given its premiere this Thursday at the Royal Academy of Music and then

performed on June 3 at the International Handel Festival in Göttingen, Germany.

Jacqueline Riding, the director of the Handel House Museum, said: "With the discovery

of this unknown work and the opening of the composer's home as a museum this November,

this is an extraordinary year for Handel."

Unless

explicitly specified otherwise,

this page and all other pages at this site are Copyright © 2015 by David

Vickers and Matthew Gardner

GFHandel.org credits

Last updated:

August 30, 2020

· Site design: Duncan Fielden, Matthew Gardner and David Vickers

|