Nabal is a curiosity from 1764. It has words by Thomas Morell and others, with music

taken from various works by Handel, with recitatives and perhaps one air by

John Christopher Smith Jnr. It was a commercial venture seeking to tap into a

continuing demand for Lenten oratorios by Handel after 1759, the year of his

death. A few of his sacred works had been revived in his last years, and

Nabal seems to perpetuate this tradition of musical archaeology. Handel

had collaborated with Morell as librettist for The Choice of Hercules

and for The Triumph of Time and Truth, both of which revived

pre-existent music by the Master. We need not condemn, therefore, Morellís

attempts to prolong the aesthetic of that collaboration after 1759. With

regard to the creation of Nabal, Morell appears the prime mover, with

Smith, an experienced musician under Handel's tutelage and direction, as music

arranger, director, and composer of the recitatives.

Importantly for lovers of

Handel's music, Nabal represents something of special interest: Morell

sought to arouse interest in the treasures in Handel's works, other than the

oratorios, which had not been heard for some time. Nabal is thus the

first attempt after Handel's death to develop interest publicly in the

composerís opera music. The Christian dedication in Greek text on the

front page of the wordbook for Nabal says "He is not dead having died",

though it is conceivable that Morell also intended it to refer to Handelís

music. The choice of musical numbers shows sensitivity on the selectorsí part

towards the riches that Handel had left behind.

Morell was Handel's final

librettist and author of more librettos for the composer than any other. With

his unique insight into the composerís world, he was able to provide a new

context for old arias, duets and choruses. No accompanied recitatives from the

operas or oratorios found their way into the Ďnewí work they relied on the original surroundings for their meaning Ė and the music

considerably determined Morellís choice of verse form, metre, diction, and

syntax from which to make a viable narrative. He provided English words for

Italian arias with ease, adapting with some facility the operasí Italian

iambics to their English counterpart, including careful placing of Handel's

decoration of Italian verbs or abstractions on an appropriate English

equivalent or sound.

Nabal has no pretensions. It has enough light-hearted numbers and contrasting

contemplative ones to provide a pleasant, if short, evening in the theatre.

The text makes no attempt to plumb the depths of human nature Ė the peculiar

territory in the oratorios of Handel and his librettists working together.

Reading twenty first-century dramatic values into Nabal misses the

point. We are much more aware of Handel's operas and oratorios than were

Morell's contemporaries, and we have probably heard some of the composerís

works more frequently than he ever did. To blame Morell for 'poor' words and a

lack of 'drama' contorts his prime concern, which was to hear some agreeable

music in a theatre. Nabalís performance in 1764 allowed some of its

audience their first opportunity to hear an orchestra play numbers which had

previously been available in printed score only.

The story of Nabal is derived from 1 Samuel 25, which might be

essential reading for us in order to get the gist, but not for Morell's

audience, who knew their Bible much more thoroughly than we do today. Musical

delight mixes uneasily (for us) with stiff Protestant doctrine. For the

often-penurious Morell, however, the hoped for income stream did not flow from

Nabal, and though he made a further attempt with Gideon in 1769,

after that there was no more on the libretto front from him.

The Story

ĎNabalí means Ďfoolí in Hebrew, and the story of this rich landowner who requites evil

for Davidís good and then dies of a stroke provided Morell with just enough

incident to contextualise the musical selection from the operas and oratorios.

He illustrated the Biblical theme of a personís duty to repay good with good

and how the land represents Godís relationship with man. Simple situations

were contrived for singers to display contrasting emotions in the voice.

Part 1 of Nabal deals with the Lord's goodness to man and manís

gratitude for the boon. Contrast with such grace is provided by Nabal's

country pleasures, which are carnal and not religious. Part 2 sets up a

confrontation between David's emissary Asaph and Nabal. Asaph pleads for food

to ease the famine in David's land; it is a gift requested in return for the

past favours of protecting Nabal from his enemies and not plundering his

estate while doing so. Nabal rejects the obligation, questioning David's

authority and right of expectation, and thus God's law of righteous

reciprocation. The chorus of Nabalís attendants (farmers?) celebrates the

productivity of their sheep. Meanwhile, Abigail, Nabal's wife, "united to a

Churl", yearns for a life of spiritual comfort. She is warned by a shepherd of

the approach of David's army bent on revenge for Nabal's ingratitude. Aware of

David's plight, her ploy is to approach him "Charg'd with Provisions" and

plead that Nabal's people should not suffer on account of their master. Her

ploy appeases David's anger.

Part 3 begins with

Nabalís death agony (Smith's recitative here is reminiscent of Purcell's cold

music in The Fairy Queen). His death is announced and his attendants

reflect on the "slow Degrees [of] the Wrath of God". Abigail asks David for

protection. (She is announced as a "relief" in Martini's version, though for

Morell she is Nabalís "Relict".) Her demeanour engages David's impressionable

emotions, love ensues, and the oratorio ends with a celebration of the "Thrice

happy, happy Pair". The "Thrice happy Sheep" in Part 2 and the loving pairís

threefold happiness testify that God's creatures are finally in harmony with

the Lord.

The Performance

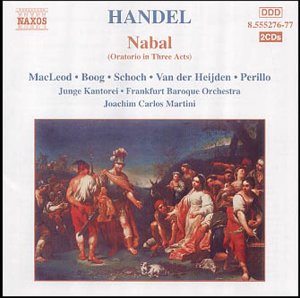

This is the first recording of Nabal. Filling a gap is all very well, but the

sadness of this recording is that it misrepresents Handel, Morell, and Smith.

Is Naxos cashing-in on the upsurge in interest in Handel's music? Perhaps

their commercialism is no different from Morell and Smithís, yet this is a

low-key performance by youthful voices in a work which needs all the help it

can get. And neither is the performance an accurate rendering of Morellís

intentions (I have not accessed Smithís autograph score, so cannot comment on

the musical arrangement). Morellís wordbook for Nabal notes those airs

and duets that were to be given repeats of the A section, but Joachim Carlos

Martini, the conductor, adds repeats where they are not marked in the original

wordbook. What is worse, horror to relate, Martini adds a whole raft of ballet

music, a genre utterly alien to a Lenten oratorio in English. Morell the

parson would not have countenanced ballet in a sacred work.

The singing does not get off to a good start and no improvement follows. Knut

Schoch is a weak David. Though his voice is tenorino, a voice

especially suited to the softer passions, he does not muster sufficient

feeling in the airs to render them persuasive. David's description of the

Lord's gift of manna (using Grimoaldo's "Prigionera ha l'alma in pena" in

Rodelinda) comes across as merely sounding the notes rather than acting

out the situation. It has to be said that for all performers on this recording

no one item is praiseworthy, though Maya Boog as Abigail supplies a pleasantly

light and bright soprano throughout, with some tasteful decorations in

repeats. But the weakest link is Stephan MacLeod's Nabal, which fails to

convey any notion of villainy. His deficiency is assisted by the intrusion of

organ continue for his recitatives. It seems to be acceptable these days to

accompany anything remotely Christian with an organ, but surely not an

unrepentant Nabal. The sound is awful because its sobriety clashes with

Nabalís nastiness. Martini gives him a buckshee da capo in "Still fill the

Bowl" ("Finche lo strale", Floridante) which prolongs our aural

agonies. Francine van der Heijden competently sings Asaph, and Linda Perilloís

Shepherd is also acceptable.

Then there is the chorus, Junge Kantorei. Their irregular phrasing in "The

Righteous shall be had" ruins one of Handel's most lyrical choral movements,

and they labour breathily with Morell's Christian paradoxes in the chorus "The

Lord, our Guide" (Joseph), failing to point the words and thus the

meaning. The chorus is sometimes either early or late on its entry. As for

Martiniís conducting, the interludes of dances, though irrelevant nonsense,

are spiritedly executed. And an organ accompanies the pastoral air ("Replicato

al ballo" (Il Pastor Fido and The Triumph of Time and Truth)

which should sound "Gay and Light". This whole scene in Part 2 lacks the

Hedonism Morell intended and therefore falls considerably short of what Morell

and Smith must have hoped for. By the way, Morell notes that the first

da capo in the piece should be the air "Sing we the Feast" ("Bella sorge",

Arianna).

The orchestral sound of the Barockorchester Frankfurt is slender. Why is it assumed that Baroque music

requires an 'authentic' thinness of string sound? It doesn't. Handel's band

was large, accused of being noisy (Pope's The Dunciad IV gives some

evidence for this). Martiniís oboes are too often indistinct, and in the

chorus the whole wind band is not sufficiently assertive. Oddly, the organ

does not support the choral parts (and was arguably used in the pastoral

choruses in The Triumph of Time and Truth, but not here). The harvest

scene in Part 2 lacks zest Ė and where are the horns?

Oh, the pity of it all. I suppose we should be grateful to hear Smithís recitatives and ďWhen Beauty

Sorrowís Livery wearsĒ (music by Smith?). The CD gives no information on the

work or on Smithís part in the enterprise. Had Martini's role been curatorial

(to play the notes and words as written by Handel, Morell, and Smith) we could

have celebrated his achievement, but as presented on this CD his efforts are

to be regretted.