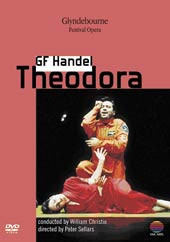

Here is a chance to purchase a

record of one of the finest stagings of ‘opera’ in the late twentieth

century. Without a doubt, Theodora at Glyndebourne was an astonishing

success: the critics raved, it was a sell-out, and it won many converts to

Handel as a dramatic composer of the first rank. A

review of William Christie’s musical interpretation of this oratorio is

already on gfhandel.org (albeit with a differ cast), so this review

considers visual presentation. First, the challenges. What Sellars has

chosen to stage is essentially unstageable. Where else in music is there a

piece that concerns itself with powerful people demanding obedience to the

State and how other people, through their actions, demonstrate that private

conscience and belief cannot be subordinated to secular authority? This all

sounds unpromising drama. Morell and Handel between them produced a flawless

work of art, and this staging, though contrary to the character of unstaged

oratorio, is a theatrical triumph because it is constantly true to its

spirit.

Secondly, the solutions. It

is an interesting artistic endeavour for a director of the stage version of

a drama to direct it for video. He cannot hope to capture the total visual

spectacle he arranged for the theatre audience because he cannot give a view

of the whole stage and its contents, conductor, players, and audience.

Instead, we are given exactly what the director wants his video audience to

see. He chooses either long-shots or following-shots for us to get a sense

of the whole, medium-close-ups for groups, or close-ups of individuals at

moments of intensity; we get broader views of the chorus when they take over

from the soloists. This director is rightly self-indulgent, selecting his

favourite moments for sustained visual concentration. Sellars avoids those

details we involuntarily see when a chorus member scratches her nose, a

principal moves awkwardly into position, or orchestral players waiting their

next turn.

The key aspect of this

staging is its simplicity. There are no spectacular effects, no magnificent

ensembles or crowd scenes; the scenery is abstract, formed of ‘bottles’ of

various sculptural shapes that are moved at private moments in the drama to

create new still-lifes. Their ‘fragility’ is a metaphor for political power

(in Act 3 Valens has them as a backdrop). Manhandling the scenery creates

moments of silent tension in which the audience has to reflect on what is

going on and what these shapes and their positioning can possibly mean.

Sellars gives us a winning lesson in semiotics, with signs abounding in the

gestures, grouping, costumes, ‘scenery’, and the lighting, and with which

Sellars masterfully manipulates the video audience. See how his chorus

performs in real time, how they enter into shot, miming conversation, moving

around and sitting down in the apparently haphazard manner of unstaged

people. But when they sing, their verismo acting gives way to choral miming

and extravagant gestures. Somehow it all works; it convinces by the force of

the commitment of everyone involved. When the camera is on them, no one

blinks. To prevent our getting bored, the director observes the commonplace

precept of media that eight seconds is the maximum span for each unmoving

shot.

A review should not be an

essay, so a few details and examples will have to suffice to illustrate the

delight that this recording affords. Sellars shows an unerring knack for

representing impotent frustration --- from Septimius’s struggles to

understand Christian motives, to Valens’s exasperation in Act 3. Though Act

2 begins in over-the-top vein, it sobers up for Theodora’s prison scene,

which Sellars stages in a ‘cage’ of light surrounded by darkness, with no

theatrical window bars or walls. Theodora circles her ‘cage’ as if a fretful

animal. Irene breaks this illusion by singing as if in a dream that Theodora

is having. Touches of this forceful kind flourish in this staging. The way

that Lorraine Hunt sings Irene is a welcome reminder that Handel often

employed singing actresses, no doubt because of their ability to animate

their parts and inject into his music a personality that was truthful to the

character. In this production the singers, all of them, are excellent actors

of the sentiments they sing.

Striking tableaux feast the

eyes. ‘As with rosy steps the morn’ is played against a dim stage with Irene

centre stage, her gestures accompanying the words. And it must be noted that

all actions by all characters in this staging arise from the words, not the

music, which is the key to Sellars’s success. There are odd indulgences on

the way, though, such as the syringe metaphor, first seen in close-up when

morphine is prepared for Valens during his phony heart-attack, and when it

reappears to be administered as an analgesic to the doomed Christian couple

at the end of the drama.

The finest moments on this

video occur at the end. The chorus ‘How strange their ends’ is one of

visible stupefaction. We see a demonstration of Spinoza’s lesson that when

vanquished by love hate passes into love. The final duet and chorus are

emotionally draining --- no participant on stage appears to escape from the

same purging of the emotions, and Sellars does not take our eyes away from

the scene for a moment. In our painful world the passing of hate into love

is an antidote to the paralysis of utter despair --- look at Irene’s face,

in the last shot we get of her, as she looks up in hope. Handel, Morell,

Sellars, singers, players and theatre designers, Stoicism, Erastianism, the

teachings of the early fathers of the Church, anti-Deists, all superbly

blend in a masterpiece of music-drama. This DVD Theodora will never

be surpassed.

1996

Interview with Peter Sellars