(For Philippe Gelinaud's review of the Arthaus Musik DVD recording, click

here.)

Handel’s intense tragedy Tamerlano was first produced at the King’s

Theatre, Haymarket, in London on 31st October 1724, yet Handel had commenced

composing the score much earlier on 3rd July 1724. This unusually long

digestion period allowed Handel to make substantial alterations to his

autograph manuscript, especially after the tenor Borosini arrived from Italy,

bringing with him some good ideas about the role of Bajazet (the central

character of the opera, and without doubt Handel’s greatest operatic tenor

role). Therefore Tamerlano has an exceptionally complicated composition

process, and there are at least three distinct and definitive versions:

- The completed first draft that can be constructed from Handel’s

autograph manuscript completed on 24th July 1724. This features several

musically engaging numbers at the end of the opera that function as a

conventional lieto fine (i.e. “happy ending”) such as a unique example of a

castrato duet, and locates Asteria’s aria “Cor di Padre” at the end of Act

II.

- Handel’s extensive revision that was actually performed in October 1724,

as contained in insertions and alterations in the autograph, Handel’s

conducting score, and the original London printed libretto. This featured an

expanded role for Bajazet, and a condensed ending to Act III that has

greater dramatic realism and bitterness. Asteria’s “Cor di Padre” is

relocated to the opening of Act III where it gains enhanced poignancy. The

relatively happy end of Act II is instead completed by Asteria’s new aria

“Se potessi”.

- In 1731 Handel revived the opera, but shorted many recitatives. The

minor bass role Leone was sung by the exceptional Montagnana in 1731, so

Handel inserted the splendid aria “Nel mondo e nell’abisso” for him.

The most artistically satisfying scheme for Tamerlano is certainly

the version prepared for the first performances. Handel’s decisions about

Tamerlano made between July and October 1724 all demonstrate an awareness

of the dramatic power of the tragedy. His decision to omit some fine music

from the last few scenes demonstrates his willingness to sacrifice superficial

entertainment value of the music for the benefit of the artistic quality of

the opera. It is therefore to be regretted that not one of the several

recordings of this magnificent opera manages to accurately represent Handel’s

intentions. Of the recordings previously available on CD, Malgoire’s

idiosyncratic understanding of the sources resulted in extensive cuts and

several misplaced items, and Gardiner’s persuasive performance is based on a

convoluted inauthentic mixture of versions that attempts to present almost all

the music of the autograph and first performance versions.

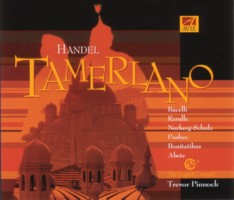

This new recording by Trevor Pinnock is as musically and dramatically

convincing as any previous version, although an initially harsh verdict is

that it is a wasted opportunity due its minimal advance of our understanding

of the opera as Handel intended it to be heard. Handelians will have wanted a

complete October 1724 version, and, once again, have been frustrated: the 1731

bass aria for Leone is included, “Cor di Padre” is located at the end of Act

II as it was in only Handel’s first draft, and several long recitatives are

also shortened following examples in Handel’s conducting score (a perfectly

reasonable approach to live performance in the modern theatre, providing you

are worried about union rates rather than patronising the level of interest

from your audience).

Any potential confusion about Tamerlano had already been irrevocably

clarified by the research of Terence Best, who provides the excellent booklet

essay for this CD. Furthermore, Pinnock used Best’s entirely reliable edition

of the score. Yet either Pinnock or Miller decided not to follow any authentic

version by Handel 100%, due to reasons that one must charitably assume are

practical requirements beyond their artistic control. Perhaps such reasons

might be condoned under less than ideal circumstances: live recordings cannot

last much over 3 hours without costing the orchestra a fortune in wages for

the players. Also, the opera houses where Miller’s production was performed in

June 2001 all believe that operas organised by their librettist and composer

into 3 acts should only have one interval in the middle of Act II. In addition

to this, in a radio documentary broadcast in association with this

performance, director Jonathan Miller proudly announced his refusal to learn

how to study music scores when he can use CDs instead when preparing his

staging. This explains a lot about the mildly erroneous musicological

decisions that have been made.

Yet some listeners may not be interested in looking for a faithful

representation of one of Handel’s most brilliant creations as a dramatist, and

the good news is that Pinnock’s performance is generally a positive and

predictably sensible yet rich musical experience. The tenor Thomas Randle has

recorded plenty of Handel before, but seems better cast as Bajazet than any of

his previous roles. His strong chest voice and enthusiasm for the sentiments

of the Italian text result in some exceptionally pleasing moments, such as his

climactic aria “Empio, per farti guerra”, and a phenomenal suicide scene in

which he has taken poison in order to escape Tamerlano’s relentless tyranny,

and consoles his distraught daughter Asteria (Miller also observes the stage

directions in the original libretto and has Bajazet die offstage after his

exit - characters actually dying on stage is a trait of nineteenth century

opera, and does not belong in opera seria).

The other great performances in this performance of Tamerlano are

unfortunately the less prominent dramatic roles, such as Anna Bonatatibus’

lyrical Irene and Antonio Abete's assertive Leone. Graham Pushee provides some

sensitive interpretative musicianship as Andronico, but does not always have

the intonation or depth of expression to make his contribution first class.

Monica Bacelli’s performance as the titular tyrant is vocally efficient but

lacks the requisite personality, and Norberg-Schulz’s Asteria is competent

without being sufficiently communicative. The biggest star of the performance

is The English Concert, whose phrasing and textural colour are consistently

perfectly judged and stylistically wise. Pinnock - largely by a sense of his

absence and willingness to trust his players - allows Handel’s orchestral

textures to flow completely free of gimmicks and shock or novelty value.

Like its predecessors, this is not the Tamerlano that Handel

deserves. But it is an interesting and valuable contribution to the catalogue.

One cannot help but be pleased that Trevor Pinnock and The English Concert are

making recordings of large scale works again after an absence of too many

years that has deprived us of their warm and intelligent musicianship. The new

independent record label Avie must also be applauded for the excellence and

quality of the booklet, packaging, and for their support of a recording

project that has a refreshing lack of ego and conceit.

*Recorded during live performances of Jonathan Miller’s

staged production at Sadler’s Wells, London. Available commercially -- or

directly from The

English Concert at at a discounted price.